YESTERDAY afternoon, The Times published a story that revealed that a German historian had discovered that the founder of the modern Olympics, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, had received a donation of 10,000 Reichsmarks from Adolf Hitler to thank him for praising the Nazi regime for hosting the forthcoming 1936 Olympics.

It’s a good story, but to my eyes – and to those who have kindly read my book Berlin Games – it’s not news. That book was published sixteen years ago, and in it, I revealed how the Nazis had effectively bribed the impecunious de Coubertin in May 1936 to endorse the Olympics.

Naturally, when I saw The Times story, I got into a bit of a huff, and tetchily tweeted about it, complete with photographs of pages from my book to show that I had got there first, and that the German historian hadn’t really discovered anything new.

After sleeping on it, I now wonder whether I should have been the bigger man, and just let it go. I don’t suppose that the historian had been acting in bad faith, and I suspect it was more a case of oversight. I’m not going to harangue him for not reading my book – it is sadly not yet published in German – and besides, the historian’s research has added a new element to the episode.

However, being the bigger person and letting things go, is not, I am afraid in the nature of many historians when they feel another historian has stolen a bit of their glory.

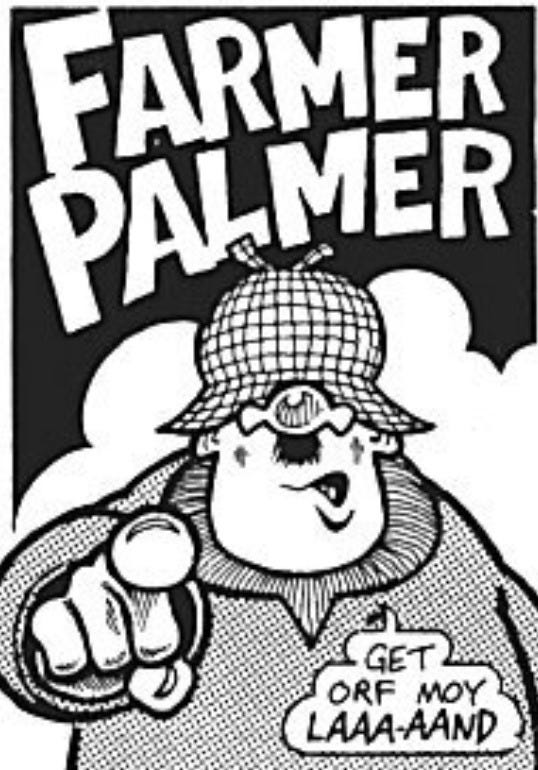

Although being peeved about such a thing is surely understandable, what is surely less acceptable is when historians get immensely proprietorial about other historians writing or commentating about what they see as ‘their’ topic. Fans of Viz magazine will readily equate this behaviour with the similarly proprietorial Farmer Palmer, who angrily entreats people to get orf his laaa-aand.

It’s easy to see why historians get like this. They can spend years – perhaps all their professional lives – researching, writing and broadcasting about a topic, and as a result, they feel an immense sense of ownership. So when some whipper-snapper turns up and starts looking at the same topic, it can feel like trespassing.

Of course, in an ideal world, historians should actively welcome as many people as possible researching ‘their’ topic, as that will clearly increase understanding, but many historians – including myself! – are all too human, and want our topic all to ourselves. (I really hope scientists don’t behave like this. Perhaps they do.)

Perhaps the most egregious example of this sort of ‘farmerpalmerism’ was the treatment my friend Hallie Rubenhold received from the self-styled community of ‘ripperologists’, who spent years haranguing her as soon as they found out she was writing a book about Jack the Ripper’s five victims. The ripperologists clearly did not like Hallie ‘straying’ onto ‘their’ historical topic – in short, she was a trespasser.

Things don’t often get this bad, and historians do try – but often fail – to behave in a collegial fashion and welcome through gritted smiles when a rival discovers something they’ve missed.

So I promise that the next time someone claims to have discovered something about one of ‘my’ topics, I shall do my very best not to moan about it on Twitter.

Even if I got there first.

I read Rubenhold’s book and listened to her podcast, both fascinating. The response from largely male (I imagine) Ripperologists was simply outrageous. I’m not an academic or historian but I do think it’s important that due credit is given to whom ever did the original research. A later writer might something new but they should acknowledge their launching point. As an aside I think we are living in a golden period; fabulous new books, terrific on line resources, and great presentations such as yours and your buddy Adrian Weale’s.

Great Post Guy & one I can empathise with. I spent my doctoral studies writing the biography of Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy, legal expert on marriage & family law & militant suffragist. My book was published in 2011, when few historians (let alone the general public) knew EWE existed. Now, in 2022, she's featured on the Fawcett statue plinth in Parliament Square & has her own statue in Congleton, Cheshire where she lived for 50 years.

In suffrage circles EWE is now a "household name", and school children in Cheshire know her story. I recently met an A'level student who is trying for Oxbrige. She told me she hopes to write Elmy's next biography! At first I was a bit taken aback, EWE was "my" topic, but then I thought again. If history is to evolve, new interpretations (well informed ones only of course,) need to be encouraged. And I'm too much in my dotage to want to write from another angle. Before too long I found myself sharing with this bright young scholar just how she could write about Elmy from a totally different angle, making something new of the sources by using a different methodology. I actually got a feel good feeling into the bargain!