"I think about him every day – I suppose in a way I loved him."

Brian Hewett worked closely with Field Marshal Montgomery in the 1950s as his shorthand typist for over two years. Last month, I went to Paris to hear what he remembers of his remarkable former boss.

IT IS early Saturday evening in Paris, and the light is turning golden. It is warm for mid October, and the boulevards and cafés are thronging with people. The mood of the city feels happy, relaxed, and fun. But in a small flat on the top floor of an apartment block in the Montparnasse district, an 85-year-old man is close to tears.

“I think about him every day,” he says. “I suppose in a way I loved him. Not in a romantic way, but more like a father and son relationship. I look at his picture every day. He remains very much a part of my life.”

The man in the flat would be the first to admit that he is very far from being famous. His name is Brian Hewett, a former teacher of office skills such as typing and shorthand. However, the man he is talking about, the memory of whom brings tears to his eyes, was very famous indeed.

For he was none other than Britain’s most venerated military leader of the Second World War – Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

It is now eighty years since the Battle of El Alamein, Montgomery’s decisive victory in North Africa over his arch foe, Rommel, which turned the tide of the war and made ‘Monty’ a household name.

Winston Churchill famously said of Monty’s victory at El Alamein that it was “Not the end, not even the beginning of the end but, possibly, the end of the beginning.”

Ever since that fateful battle, Monty has enjoyed a mixed reputation – loved and respected by the rank and file, but often regarded as being arrogant and insufferable by those who worked closely with him, including Winston Churchill himself, who once famously remarked of Monty that he was ‘in defeat, unbeatable; in victory, unbearable’.

To discover the true face of this legendary figure, it is best to talk to the dwindling band of people who knew him well. And that is why Brian Hewett is so special, for he is one of the few people alive who did indeed know Monty well – and who really got to discover the man beneath the famous double-badged beret.

The son of a grocer and trader, Brian was born in 1937 and raised in Caterham in Surrey in a religious family. There was an expectation that he would join the Salvation Army as a bandsman, but the teenager found that he had a talent for what were then known as ‘commercial subjects’ – such as typing and shorthand – which he had acquired at Pitman’s College in Croydon.

As he approached the age of 18 in 1955, Brian knew that two years of National Service were just around the corner.

“I decided that it was better to join up for three years as a regular soldier because I would have more control as to how my service would be spent,” Brian recalls in a bedroom in his flat, complete with signed and dedicated pictures of Monty on the wall, and even a Monty-shaped mug on the table.

“As I was walking back from school one day, I nipped into the Army Recruiting Office, gave evidence of my shorthand and typing, and a short while later I was enlisted as Private Brian Hewett of the Royal Army Service Corps.”

Towards the end of that year Brian was summoned up to the War Office in Storey’s Gate in London, where his skills were assessed. At that point, he had no inkling as to why. After a wait, a major appeared in the waiting room and said:

“Private Hewett, I have telephoned to France. You are appointed personal shorthand-typist to the Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe, Field Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein!”

To this day, Brian is not entirely sure why he got the job, as he thought that a rival candidate was better qualified.

“However, as he had been a journalist, it was perhaps felt that working in such a sensitive position might have given him split loyalties,” Brian says, wearing his regimental tie. “And because of the Salvation Army, I also didn’t drink or smoke, which may have made me more suitable for Monty, who was of course a teetotaller.”

It is hard to overestimate just how colossal a figure Montgomery was in Britain in the mid-1950s.

“His reputation was just astronomical,” says Brian. “He was this huge figure.”

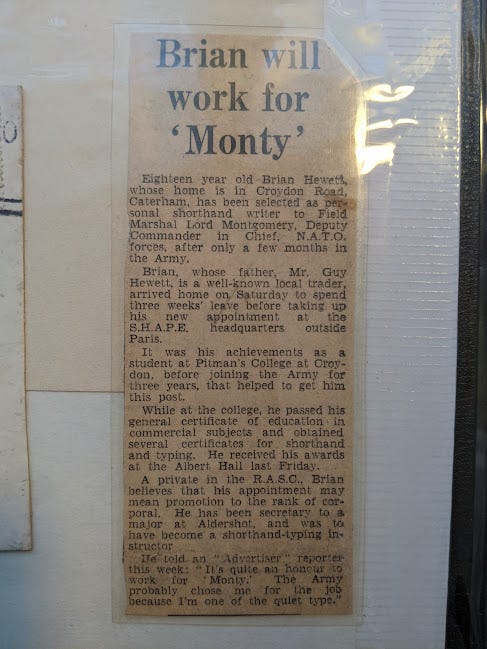

Brian’s appointment even made the local newspaper, in which he was quoted as saying that he was probably chosen for the job ‘because I’m one of the quiet types’.

This was doubtless the case, and it made Brian the polar opposite of his new boss, who famously loved the limelight, and was regarded as quite the showman. Indeed his appetite for self-promotion infuriated both his allies and his superiors during the war.

Churchill’s Chief of Staff General Hastings Ismay, was particularly scathing about Monty: ‘I have come to the conclusion that his love of publicity is a disease, like alcoholism or taking drugs, and that it sends him equally mad.’

Even Field Marshal – late Lord – Alan Brooke, wartime Chief of the General Staff – and Monty’s ultimate commander in the war – who admired Monty, referred to his ‘lack of tact and egotistical outlook which prevented him from appreciating other people's feelings.’

And at first, it seemed as if, in the decade since the war, Monty had not mellowed.

When a nervous Brian first met him in early 1956, Monty was Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe (DSACEUR), residing at the grand surroundings of Trianon Palace Hotel in Versailles.

“I remember being ushered through the sound-proof double doors of his office,” Brian says, now smiling at how tense he was. “This was the holy of holies, and I stood rigid before his desk. He then let me stew there for two minutes while he looked through some papers. Eventually he looked up, and said, ‘Hewett! What are you afraid of?’ ‘You sir!’ I replied. He then just smiled and passed me some documents and ordered me to destroy them.”

This would be Brian’s first job for the Field Marshal, and in some ways, it was a test of his confidentiality.

“These were the days before shredding machines,” Brian recalls, “and I had to shred all the documents by hand. They were all clearly top secret, and some had been written by VIPs. About mid-way through, I came upon a letter than began with ‘Cher Monty’, and at the bottom, signed in green ink, was ‘Charles de Gaulle’.”

Realising that it would make quite the souvenir, Brian tore out the signature and put it in his back pocket.

However, a few minutes later, he had an attack of conscience.

“I thought to myself that the reason why I had been selected to work for the Field Marshal was because I wasn’t the type to do things like that, so I took the signature out of my back pocket and destroyed it.”

Monty evidently trusted him, for he soon gave him the job of typing up his handwritten memoirs.

Most days, Monty would personally hand Brian some pages of his neatly-written recollections, to be typed up with four carbon copies for eminent proof readers, who sometimes included none other than Winston Churchill.

At one point, Monty even relayed to Brian a criticism made by the former war leader.

“Hewett,” said Monty, “Winston says that there is no hyphen in the words twenty-fourth and thirty-seventh.”

“The ground could have swallowed me up,” Brian says smiling. “Here I was, the lowest of the low, involved in an exchange between the two greatest war leaders alive. It felt like quite a place to be.”

Working on the memoirs – which were not strictly military business – would prove to be tough work, both physically and emotionally.

“I would often be up until two in the morning typing up the memoirs,” Brian remembers, “and they were often very moving. I remember one passage in which he was recalling how if he attacked in a certain way with one unit, he would be creating two thousand widows in Newcastle, and if he attacked in another way with a different unit, he would be creating two thousand widows in the Midlands. That really brought home to me the decisions that he had to face during the war. I remember as I typed that passage it made me cry, and even now it makes me tearful to think about it.”

It is not the only moment that tears spring to Brian’s eyes as he recalls his time with Monty.

Like his hero – whose wife tragically died in his arms from septicaemia in 1937 – Brian has also suffered the unimaginable pain of losing a family member, when he lost his 29-year-old son to suicide.

Finding himself unable to cope, Brian turned to running just a few days after his son’s death as some form of therapy, and recently, aged 85, Brian ran his 443rd competitive race. Along with his Monty memorabilia, the numerous trophies that he has won are all around – proof perhaps of a single-mindedness that he shares with his erstwhile boss.

Brian would be reminded of Monty’s own loss every morning, because it was the young private’s job to deliver the Field Marshal his newspapers to his solitary bedroom every morning, along with any pages of his memoirs that he had typed up.

Brian occasionally saw flashes of the abrasive Monty: “I found him mercurial,” he says diplomatically. But adds that the great man was “thoughtful, sharp as a needle, compassionate, clear-thinking, decisive, full of fun, and extremely professional”.

Brian remains deeply conscious of the privilege of seeing this revered national figure at some of his most intimate moments. At Monty’s home in Hampshire, where he continued to type up the memoirs, he found himself staying in Monty’s son’s bedroom.

Life there with Monty could be unpredictable.

“One morning I noticed that the loft ladder had been left in position on the landing,” Brian recalls with a twinkle in his eye. “Curiosity got the better of me and I climbed up and found a biscuit tin. I opened it up, and there was Monty’s famous double-badged beret! I decided I had better put it back and returned to my typewriter. A few minutes later, I heard a gunshot coming from below me, and I saw a pigeon dying on the lawn. Monty had shot it from the window below me, and I then heard his unmistakeable voice: ‘Chef! Pigeon pie for lunch!”

As well as such jocular moments, there are others that Brian recalls with some regret.

On one occasion, Monty asked one of his two chefs to climb up a ladder to fix a roof tile, but the chef explained that he was not insured to do such a thing, and refused. Instead, Monty had to replace the roof tile himself, not necessarily the easiest of jobs for a man approaching seventy.

“I wish he had asked me to have done it,” Brian recalls, again with his eyes moistening. “I would have done anything for that man.”

Did Brian find Monty’s domestic situation somehow sad or lonely?

“At the time, I was just a very young man, and had been raised in quite a sheltered way,” says Brian. “So I wasn’t really thinking about Monty’s emotional life. But in retrospect, I think he must have been lonely. But instead, he threw himself completely into being a soldier. He was completely dedicated to his work.”

Monty revealed a considerate side when, at the end of Brian’s time at Monty’s home, the Field Marshal told him that as he had done three weeks work in just two, he could have a week’s leave, and gave him a pound note from his wallet. Brian refused to accept it.

“This is unofficial leave,” Monty insisted. “You company commander in Paris knows nothing about it, which means that you will have no travel warrant for your fares. So take it!”

As Brian understandably says – “further hesitation was out of the question”.

In February 1958, Brian had his last meeting with Monty. Knowing that the Field Marshal was going to leave the army later that year, Brian decided that he would leave as well. That final encounter was unemotional – this was the 1950s after all – but Brian was very touched when Monty supplied him with the telephone number of a Lieutenant-Colonel who now worked for a newspaper, and was able to offer Brian a job. Although Brian did not take the job, eventually going into teaching, he was touched at his boss’s thoughtfulness.

Some years later, when Brian spotted a photograph of Monty in the newspapers in 1967 when the 80-year-old Field Marshal was attending what would be his last Alamein reunion in Egypt. Brian got hold of a copy of the photograph and sent it to Monty asking if he would sign it.

A short while later, an envelope appeared, written in the neat handwriting that Brian knew all too well. Monty had indeed dedicated and signed the photograph. Today it hangs in pride of place of Brian’s bedroom wall, covered with a piece of material to stop the ink fading in the sun.

“It touches me more than you can imagine that Monty made such an effort for me,” says Brian. “He was an old man by then, and yet he found the time to get a stamp and to address the envelope personally.”

By now it is dark, and Brian closes his albums. Even though Monty died in 1976, you get the feeling that in this small flat in the heart of Paris, his memory is still very much alive.

Ah, so this is why you went to Paris!

So many layers to unpick here to the questions of "what are we looking at/listening too"? We receive & analyse the "words & deeds" of "great men" differently these days from those of the 1950s. We turn the "undeserving" into celebrities & often vilify those who have some claim to "greatness". The terms have become warped & twisted & today's world can be a topsy-turvy place.

Montgomery was a controversial figure both in his lifetime & beyond, but for the rank & file under his command at least, he was an icon. My father's remembrances of him testify to that. For a man who served him so closely as Mr. Hewlett, that iconic status would have been magnified. And Monty did, in so many instances, "get the job done". Surely we didn't then, and shouldn't now, appoint the nation's Field Marshalls for their ability to charm over cocktails and canapés!

Any historian worthy of the name knows a personal memoir is full of subjectivity. It's just the way things are. But with careful analysis, such testimony as Mr. Hewett's can bring out a deeper charm hiding within an irascible character. For the postmodernists among us, it turns the kaleidoscope & changes the image.

Interesting. I think one should take into account some recent discussion of veteran accounts and memories and the veracity and reliability thereof. Nevertheless a remarkable experience. Certainly more noteworthy than my father’s stories of national service, some of which I’m beginning to doubt.