Secretary of genocide

Irmgard Furchner may have played a bit part, but even the minor players are guilty

JUDY MEISEL arrived in Stutthof concentration camp at some point during 1944. She was just fifteen years old. The youngest of three children, she had been born in a small town in Lithuania called Josvainiai, where her family – who were Jews – lived until they moved to the city of Kaunus in 1938 shortly after Judy’s father died. After the Nazis invaded in 1941, some 140 of Judy’s relatives were slaughtered, while she and her family were forced to share a flat in a ghetto with three other families. They stayed there for three years, during which time Judy and her brother Abe, because of their blonde hair and blue eyes, were selected to sneak regularly out of the ghetto to bring in bread and other supplies. But as the Soviets advanced in 1944, the ghetto was liquidated, and Judy, Abe, her sister Rachel and their mother Mina were all sent to Stutthof, which lay some twenty miles east of Gdańsk.

In 1990, Judy gave an interview to the United Stated Holocaust Memorial Museum, in which she described what happened when she and her family got off the train.

I remember when I arrived in Stutthof, the most horrible thing I saw is nothing but shoes and shoes and eyeglasses and shoes. It was just a huge heap of shoes, and I remember asking my mother, "What's that?" and she said, "Frage nicht 'ne Frages" [Don't ask questions]. I can remember that in Yiddish: "Don't ask questions. Why are you asking so many questions? I don't know." And, uh, we, again, had to stand in Appell [roll call], and I remember one woman, very heavyset woman, sort of her hair I can remember back in like, in a roll, and she was walking around with a big, um, oh, how do you say?...whip, 'konuiszck,' a whip, and she was just hitting, um, walking around and she said, "No one comes out alive here. You're all to be doomed." And, um, and she also said it in Polish and also in Russian, and, uh, so we could understand and, because we, a lot of us knew Russian. And, uh, then we were taken into a place, and they examined us. I can remember a hand going into my vagina and just pulling, and what we found out they were looking for gold and that, and I could...I'll never forget this woman, like two before that, had her teeth just pulled out and blood was gushing out of her mouth, and she was taken out her gold teeth. And, uh, and I can remember getting a shot, and what the shot was for I don't know. Um...later on, later on I found out, uh, that, uh, you know, when you begin to question why, and that is so we wouldn't have our period.

Throughout the interview, Judy would describe many other horrors and deprivations that she witnessed and suffered, including seeing electrocuted bodies hanging from barbed-wire fences, being squeezed into revoltingly unsanitary barracks, eating bread that consisted of little more than sawdust, and being constantly thirsty. Then came the worst moment of all, which is captured here in a verbatim transcript:

And...uh...then one day...uh...they picked us, and my mother was taken and...uh...I went with her and my sister stayed behind. They wouldn't take her and I wound. Actually, I runned after...they didn't take me. I wanted to be with my mother, and they took her into a...uh...to a place. They took us into a place and...uh... gas chamber and... uh...the guard at the gas chamber saw me getting undressed and he said, "You're too young to die. You run and I'll count to 10." And I remember my mother screaming And I started to run, and I came to...back to the barrack. And that's the last time I saw my mom. (Long, long pause) I haven't talked about it for a long time.

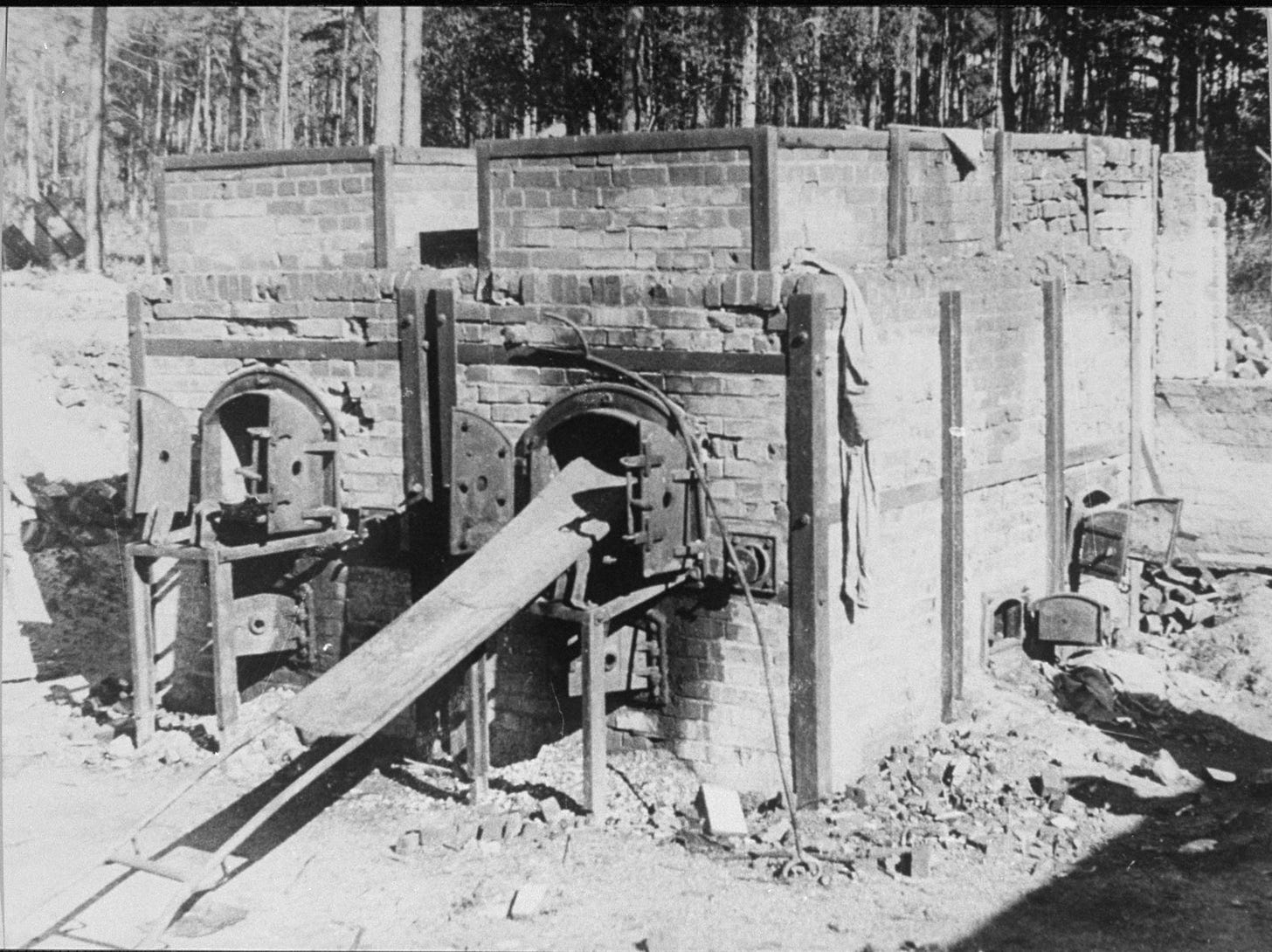

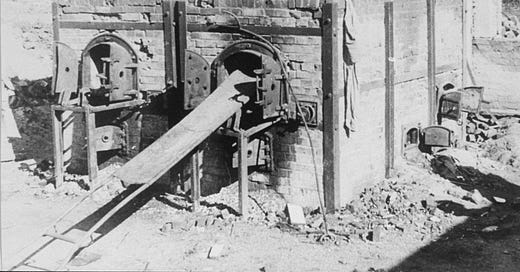

Mina would be one of some 65,000 who were killed in Stutthof, of whom some 28,000 were Jews.

Miraculously, Judy and her siblings would survive the war, and they all moved to Canada and started families of their own. Judy would die in November 2020, aged ninety-one, survived by numerous children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

My reason for quoting Judy’s experiences at length – which were sadly of course all too common – is because they remind us why yesterday a 97-year-old woman in Germany was given a two-year suspended sentence for her role as a secretary to the camp commandant, Paul-Werner Hoppe, between 1943 and 1945. Irmgard Furchner, who was aged 18 to 19 during that time, was found guilty of complicity in the murders of more than 10,500 people, one of whom was Mina Beker, the mother of Judy Meisel.

Although Furchner would deny that she knew anything about the killings and abuses, the court found otherwise, and gave her a sentence that was not a million miles removed from the nine years that her commandant received in 1957. It should be noted that over twenty of the camp’s personnel were sentenced to death in the four Stutthof trials that took place in Poland between 1946 and 1947.

There are those who argue that people like Furchner should not be tried, and that her role in a place like Stutthof was so insignificant as to remove any culpability. But this is to ignore the fact that all bureaucracies – even the bureaucracies of genocide – rely on people like Furchner if they are to function. Her role may have been small, but it was still vital. Quite simply, with no secretaries, there would have been no Holocaust.

If she were still alive, try telling Judy Meisel otherwise.

The gigantic elephant in the room is the fact that too many of the senior figures escaped justice (See your book Hunting Evil) or received ludicrously lenient punishment. For this woman to claim she had no knowledge of what was going on is preposterous.

Absolutely should people such as Irmgard be tried. They may too old for punishment to mean much at this point. We need to stick with our commitment to keep this information alive, to make it difficult for such people, and those who would repeat them, to rest easy and believe that justice will never catch up to them.