Sometimes it's the people who ask you to work for free who are the biggest mugs

EARLIER this week, I was approached by a company called Web Summit with a very exciting offer. Would I like to come to Toronto, the email asked, ‘to lead discussions on our future-focused panels as a moderator with some of our more high-profile talks’? Although I am no expert in the world of tech, I have a little experience of moderating panels, and I wondered whether word had spread about my apparent brilliance. I was circumspect, but the carrots of a trip to Canada and the potential of a fat conference fee made me think it was worth a phone call.

That call lasted precisely 1 minute and 41 seconds.

It emerged that not only was there no fee, but I was also expected to pay my own way to Toronto. But if getting there was tricky for me, then perhaps I would instead consider participating in a similar conference in Lisbon? Would that be any easier? The temptation to have it out with the caller was immense, but in the end, I (more or less) politely ended the conversation and just got on with my day.

I’ve long moaned about people wanting me to work for free. One of the pieces I’m proudest of was something I wrote for the Literary Review ten years ago, in which I moaned about festivals – even rich ones such as Hay – not paying their speakers. I like to think that my piece was my own small part in the backlash against this practice, and today it’s mostly standard that even the humblest of events is willing to offer writers a few quid.

Of course, there are still plenty of people who think they can get the services of creative types for nowt, and claim that their offer will be great for publicity or exposure blah blah yeah yeah etc etc. Believe me, I’ve heard all the gags you can make in response – including people dying of exposure, and I know off by heart the words of the celebrated Harlan Ellison video.

Until today, I always thought that the people who worked for free were the mugs, and the people who secured their free labour were the smart ones. But the case of Matt Hancock and Isabel Oakeshott has made me think again.

As most will know, the Daily Telegraph has today started its series of exposés which the paper is calling The Lockdown Files. Based on a huge leak of some 100,000 WhatsApp messages sent to and from ministers and civil servants during the Covid crisis, the messages show that the then Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, ignored the advice of the Chief Medical Officer by limiting testing in care homes, and thereby perhaps leading to many thousands of avoidable deaths.

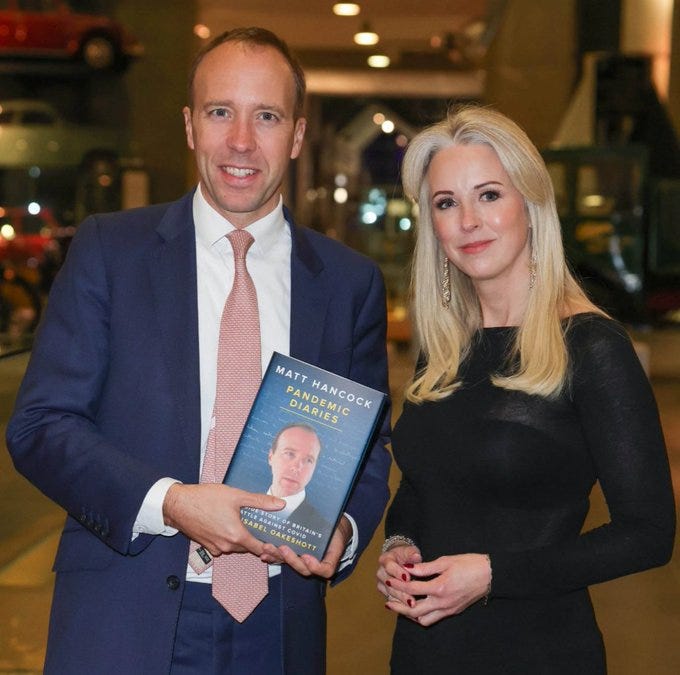

The WhatsApp messages were obtained by the journalist Isabel Oakeshott, who had been given them by Hancock himself because she was helping the former minister write his book, Pandemic Diaries, about the crisis. Although the messages were, in all likelihood, supplied under a non-disclosure agreement, it comes as little surprise to most that Oakeshott has seen fit to break that agreement.

What does come as a surprise is the knowledge that Oakeshott worked on Hancock’s book for free. When Oakeshott revealed this in The Spectator back in December, it was barely noticed, but today, her words seem positively ominous for Hancock:

In the event, Hancock shared far more than I could ever have imagined. I have viewed thousands and thousands of sensitive government communications relating to the pandemic, a fascinating and very illuminating exercise. I was not paid a penny for this work, but the time I spent on the project – almost a year – was richly rewarding in other ways.

It is possible to suppose that Oakeshott worked on year-long project because the reward came from it being so fascinating and illuminating. And it is also possible to suppose that Hancock believed that Oakeshott worked for free for this reason. After all, in Hancock’s eyes, he remains an important man with an historic story to tell – surely any journalist would work for free for such an opportunity!

In his acknowledgements, Hancock even saluted his co-author handsomely:

. . . and above all Isabel Oakeshott, whose tenacity at getting me to remember the most telling detail and gift in improving my drafting to create a compelling account are second to none.

Again, how ominous those words!

The fact is, Hancock was played. Oakeshott knew she was getting gold, and exploited the former’s minister’s haplessness, vanity, and gullibility. With the backing of a powerful newspaper and with a public interest defence, Oakeshott surely knew that any non-disclosure agreement was probably worthless. We don’t know if she always was going to leak what she was given, but the fact is she has, and Hancock was clearly wrong to trust her.

What Hancock failed to do was to ask himself this question: Why is this person willing to work for me for free? And even if he had done, it is unlikely he would have given himself an honest answer, one that might have got close to anticipating his co-author’s actual agenda. At the time, he probably even patted himself on the back that he had secured himself the services of such a high-profile writer for no money. He may have even had a laugh at her expense. Well, the laugh is now on him, and he is finally paying the price.

Would it have made any difference had Oakeshott been paid? It’s doubtful. But the point is that we should be suspicious of people – including and especially social media firms – who offer us free services, because sometimes, those who pay nothing bear the biggest costs of all.

As I said elsewhere it was unwise of Hancock to trust Oakeshott. I have never met her but I have seen her on political panel shows and she didn't strike me as a person one should have confidence in. I never cease to be surprised that organisations approach writers and historians and expect them to fork over the knowledge free of charge. Says he who has asked many a question of historians and writers.

Tricky. What is the payment for?

It wouldn't be my assumption that it would be reasonable for journalists and historians to pay the people they interview and whose tales they recycle into their article and books. So it's not the story that is important but the work.

If you are told to stand and read out lines to a camera -- as an actor is -- you might reasonably be expected to be paid to be directed to do this work. You'd have to re-do it if it wasn't upto scratch and if you didn't like the words you could say them or refuse the work. You are being paid by the person with editorial control.

If you are given a platform and given absolute discretion to say what you like and moderate how you please then you might argue that you have editorial control. Are you directing your own work? There's nothing inherently wrong with agreeing that they will provide something of value and you will provide something of value and no money should exchange hands if that is agreed and fair.

As long as it's clear up front, I don't see there's any shame in being asked to work for free, nor in politely declining that request.

This comment may be published for the cost of one glass of Burgundy. Invoice to follow.