The forgotten day in 1938 when a boat load of German veterans sailed up the Thames led by an Old Etonian Obergruppenführer

(Beat that for a headline)

IN LATE SEPTEMBER 1938, the Munich Crisis was at its height, with Adolf Hitler making increasingly shrill demands on Czechoslovakia to hand over the Sudetenland. The British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, had already flown to Germany to negotiate with the dictator, but the meeting hadn’t gone that well. There was no doubt that war was in the air, not least because Hitler had even formed a paramilitary unit called the Sudetendeutsches Freikorps to carry out raids inside Czechoslovakian territory.

While all this was happening, something very strange took place in London. On the 22 September, a German ocean liner called the Monte Pascoal steamed up to Greenwich pier, where a large crowd had gathered.

On board was a group of eight hundred German ex-servicemen, who were led by none other than a grandson of Queen Victoria, Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. The Duke was a controversial figure, to say the least. Not only was he an Obergruppenführer in the Brownshirts and a Nazi member of the Reichstag, but worse still, he was also an Old Etonian.

Who on earth was this man, and what was he doing sailing into London with eight hundred German veterans slap bang in the middle of the Munich Crisis?

Born in Esher in Surrey in July 1884, Charles Edward was the son of Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, the youngest son of Queen Victoria. As Leopold was to die at the age of thirty before his only son was born, Charles Edward came into the world both as a Duke and as a Prince of the United Kingdom.

Until his mid-teens, Charles Edward’s life was predictable for a member of the nobility, and he was educated at Sandroyd prep school and finally at Eton. However, when he was fifteen, his life was to change, thanks to Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was concerned that there was no heir apparent to the German dukedom of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. After a few candidates were considered and rejected, the coronet was eventually perched on the head of the young Charles Edward, who was taken out of Eton, moved to Germany, and succeeded to the dukedom shortly after his sixteenth birthday in July 1900.

Charles Edward’s mother was reportedly devastated.

“I have always tried to bring Charlie up as a good Englishman,” she was reported to have said, “and now I have to turn him into a good German."

Until the outbreak of war, Charles Edward managed to be both a good German and good Briton, and was even made a Knight of the Garter by his uncle King Edward VII. However, when the hostilities started, he threw his lot in with the Kaiser and served as a staff officer in the army. This saw him denounced as a traitor back in Britain, which seemed a little unfair, as clearly the Duke was going to be damned whichever way he jumped.

What was less excusable was his cosying up to the Nazis, and after calling on people to vote for Hitler in 1932, he joined the Party and the Brownshirts the following year. He was also a member of the national board of Der Stahlhelm, the paramilitary veterans’ organisation, until it was dissolved in 1935, after which Charles Edward would become president of the German ex-Servicemen’s Association.

It was in this capacity that Charles Edward led the eight hundred veterans to London in September 1938. As soon the Monte Pascoal docked, a reception party from the British Legion went on board, and a German band struck up the British National Anthem, to which the Germans all decided that it would be a jolly good idea to give the Nazi salute.

The founder of the British Legion, Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice, then addressed the visitors, telling them that it was ‘singularly appropriate that this return visit of yours should be made here in the Thames, our great London river, at the moment when our Prime Minister is arriving at Cologne on his way to visit your Führer’. He then added that it was the prayer of ‘ourselves and of you, that the meeting of these two great leaders should establish world peace on a sound foundation’.

Charles Edward responded in a similar vein, stating that he was ‘certain that our trip will further advance the friendship between our two nations, and I am fully convinced that the days we are about to spend here will be kept in lasting remembrance’.

It was then time for a spot of lunch, which the correspondent of The Times noted was held in a dining saloon that featured large swastika flags draped down its sides, and with lots of smaller flags on the tables.

After lunch, a fleet of motor launches – complete with swastikas at their bows – took the Germans up the Thames to Westminster Pier. From there, the veterans were taken through a private subway into New Palace Yard, after which they were treated to tea as guests of the British Government. Presiding over this event was Sir Thomas Inskip, the Minister for Coordination of Defence, who made a well-received speech in which he expressed the hope that was surely shared by all present that the ‘momentous conference’ between Hitler and Chamberlain would result ‘in a just and peaceful settlement’.

Once again, Charles Edward responded in kind, saying that his party had come as ‘ambassadors of the will for peace of a great and strong nation’.

After tea, the Germans went back to their boat, after which they were given a tour of the offices of The Times before they were entertained at the German Embassy.

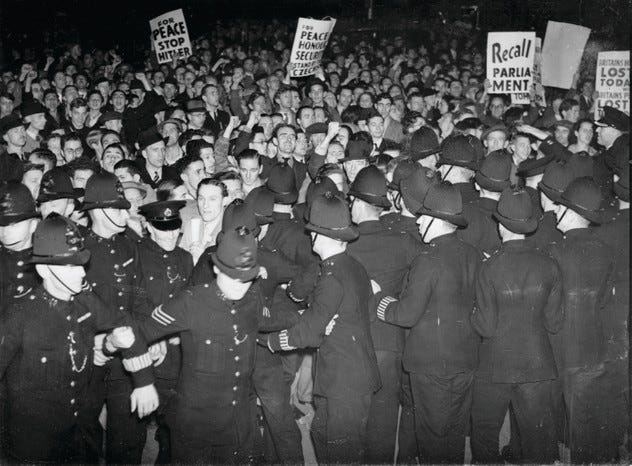

Of course, no matter how sincere and well-meaning everybody appeared to be, it didn’t even require hindsight to realise that such an event was yet another manifestation of appeasement. It should be noted that on the very same evening as the German visit, there was a demonstration on the streets of Whitehall over how much ground was being given by the British to Hitler.

It is unclear when the Germans returned home, but what is known is the fate of Charles Edward. At the end of the war he was arrested by the Americans, and he narrowly avoided being tried for crimes against humanity for his knowledge of the camps and his donations to the Nazis. In 1953, he watched the coronation of his first cousin twice removed, Elizabeth II, in a cinema in Germany, before he died the following year at the age of 69.

The ship his party travelled on, the Monte Pascoal, was bombed and sunk in 1944. She was then raised and repaired, before being seized in May 1945 by the Allies, who used her as a poison gas ammunition depot before sinking her again, in the Skaggerak.

I imagine Eton would rather forget him. I read somewhere that he had a pretty hard time of it in US detention. I’m not sure if it was family or HMG who tried t get him released but US were having none of it. Hell mend him.

Harvard has theirs too. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Hanfstaengl. BTW, may I contact you (and how) to pursue a conversation from WHW Fest that we had about some Third Reich photos I have? I don't expect you to remember, given the quantity of beer that flowed at the place and the potentially mind-altering aura given off by that poly Playboy shirt.