The truth behind The Odessa File

Was there really a shadowy Nazi escape organisation called the 'Odessa'?

THIS YEAR marks the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of The Odessa File, Frederick Forsyth’s classic thriller about a journalist penetrating a clandestine and sinister Nazi escape organisation called the ‘Odessa’. It’s a great read, and the film, which came out in 1974, is also a great watch.

However, at the risk of being a party-pooper, I’m afraid that the organisation that Forsyth describes is more a product of fantasy than reality. Having written a history of how Nazis escaped, it’s a subject close to my professional heart, and nothing gets my goat more than when people talk knowledgeably about the ‘Odessa’.

The most obvious problem with Odessa is the name. If you were organising a super secret escape network for SS men, would you really label yourself with an acronym that stood for ‘Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen’ – the Organisation of Former SS Members? No, I thought not.

The truth about the Nazi escape organisations, beneath the mushroom clouds of smoke, is that they were similar to an old-boy network, or perhaps even the loose web of terrorist cells and groups that are placed under the name of al-Qaeda.

After the war, there were countless organisations that assisted escaping Nazis, and some of these groups had names – such as ‘Konsul’, ‘Scharnhorst’, ‘Sechsgestirn’, ‘Leibwache’, ‘Lustige Brüder’ – and some did not. Instead of one big fire under the smoke, there were instead many small ones, the combination of their multiple and toxic emissions suggestive of a single large inferno. Assistance would also be provided on an ad hoc basis, sometimes by an individual or a handful of individuals rather than by a coordinated group.

However, the records do show that there was something called ‘Odessa’. Far from being the globalized tentacled monster of popular imagination, it appeared to start as little more than a watchword, and would become a term loosely ascribed to the group that took fugitives from Germany and Austria down to Rome and Genoa, and from there to Spain and Argentina.

One of the earliest recorded mentions of ‘Odessa’ is in a US Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) memo dated 3 July 1946, in which an underground organisation at an SS internment camp in Auerbach was identified. It was not called ‘Odessa’, but the word was employed as a codeword in order to gain ‘special food privileges and special food consideration’ from the Red Cross in Augsburg.

The term also had currency further afield, in towns such as Kempten, Rosenheim, Mannheim and Berchtesgaden, where it was applied to small cells of unrepentant SS members in order to provide them with a feeling of solidarity. As these groups lacked any form of organisation and leadership, the CIC was not overly troubled.

However, in November, the Czechs informed the Americans that they had caught wind of an organisation called ‘ODESSA’ that was operating in the British Zone of Occupation, and that it had held its first meeting in Hamburg in September. The following January, the CIC sent an agent into the internment camp at Dachau, who reported that there was an escape organisation operating there under the name of ‘ODESSA’ and organised by SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny, who was himself a prisoner.

‘This is being done with the help of the Polish guards,’ the agent reported, ‘[who] are helping the men that receive orders from Skorzeny to escape.’ The informant disclosed that the organisation was ‘worldwide’ and that it provided Portuguese papers for those who wished to travel to Argentina. For those who decided to stay in Germany, the group would provide employment and documentation.

However, neither the Americans nor the British were able to verify any of the informant’s claims. ‘Key personalities have been closely watched,’ the CIC reported, ‘but none of their activities have extended beyond the establishment of contact with former SS personnel in their locale.’ The CIC also felt that Skorzeny’s name was simply being used for ‘backing and prestige’.

The idea that Otto Skorzeny masterminded some secret society is fanciful, not least because nearly every move he made was monitored by the Americans, and in all likelihood, several other nations. Skorzeny was also, to be frank, neither intelligent nor discreet enough to manage a clandestine escape network.

Throughout the mid-1940s, the Allied intelligence services would receive a few more reports about ‘Odessa’, but they suggested that the organisation was little more than a catch-all term used by former Nazis who wished to continue the fight. Furthermore, the nature of the Odessa seemed to change depending on who was being interrogated. In December 1947, the CIC in Donauwörth questioned a former SS officer called Robert Markworth who had been arrested for attempted bribery. Markworth claimed that he was on a secret mission for the Odessa, the role of which was to infiltrate the Russian military government and had nothing to do with escaping.

Earlier that year, the Americans had been told by an informant that the way to contact the organisation was simply to mingle with the crowds around a selection of mainline railway stations until ‘one was accosted by someone with the word ODESSA’. The informant, whom the Americans did not know and who had simply volunteered his information, tried his luck in Hanover, where he met a ‘Herbert Ringel’, who claimed that the aim of the Odessa was ‘the planning of an eventual revolution’. Information throughout the group was spread by a network of contacts, none of whom knew the name of the next person in the chain. The method of identification was the presence of ‘three small spots in the shape of a triangle at the base of the thumb and forefinger of the right hand’.

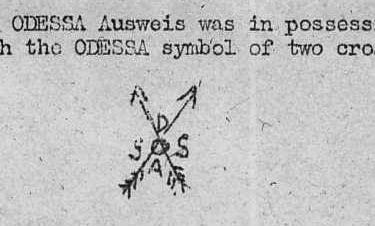

‘Ringel’ also showed the informant his Odessa Ausweis, which featured the supposed Odessa symbol on its cover: two crossed arrows laid over the letters ‘ODSSA’. The Americans graded the informant as ‘F3’, which indicated that his unreliability could not be judged, and that his information was possibly true.

In fact, what he had reported was highly likely to have been disinformation, and an amateur attempt at that. The notion that the Odessa would issue its members with identity documents was absurd, and the presence of the three spots equally so. It also seems implausible that a member of the Odessa would offer such secrets to a stranger at Hanover railway station.

The same year, yet another organisation calling itself ‘ODESSA’ was discovered in Rosenheim by the CIC, although it seemed to consist of little more than a dozen men, some of whom had previously been imprisoned for theft and possession of arms. The CIC reported that it had penetrated the group, and it noted how the word ‘Odessa’ was used as a kind of code. The leader of the group, Hans Schuchert, was described as a ‘fanatical SS soldier who always greets his friends with “Heil Odessa”.’ At a dance at the Gasthaus Plestkeller in Ziegelberg just outside Rosenheim, Schuchert requested a number for SS members. ‘Now comes a dance for Odessa,’ he said. ‘That means for the SS.’ Although some of the guests were shocked, nobody – including some policemen present – registered any complaint.

One person who became interested in ‘Odessa’ was Simon Wiesenthal. On 3 April 1952, Wiesenthal wrote a long letter to the German journalist Ottmar Katz concerning Nazi gold and how such treasure was supposedly used to finance Nazi escape routes. In the letter, a poor copy of which is housed at the National Archives in Washington, DC, Wiesenthal tells Katz about various secret Nazi societies, such as Scharnhorst, Sechsgestirn, Edelweiss, Spinne and PAX.

Wiesenthal also writes about ‘Odessa’, which, he informs Katz, is an escape organization that transported fugitives to Bishop Hudal in Rome, and from where they headed to Madrid and South America.

Wiesenthal’s source for his intelligence on the Odessa was one Wilhelm Hoettl, a former SD man who had been running highly dubious networks for the Americans until they had sacked him in September 1949. The intelligence he gathered had been evaluated as poor, and the CIC regarded Hoettl as dishonest. There was also an ongoing suspicion that he would peddle intelligence to the highest bidder, no matter on what side of the Iron Curtain the money came from.

There can also be little doubt that much of what Wiesenthal told Katz in his letter was yet more bunkum fed to him by Hoettl. It is instructive that the letter to Katz should end up in Hoettl’s file at the US National Archives. As a result, it is extremely difficult to trust anything that the gullible Wiesenthal would later present to the world concerning ‘Odessa’ and how the Nazis escaped.

Even Nazis such as Reinhold Kops, who wrote a set of candid memoirs in 1987, denied the existence of the ‘so-called Odessa organisation’. Alfred Jarschel, whose fanciful Fleeing Nuremberg is full of the most outrageous stories about Nazi escapes – including the ‘flight’ of Martin Bormann – was withering about the ‘Odessa’ story, and saw it as little more than a line Wiesenthal would peddle to journalists.

Furthermore, Erich Priebke, the former Gestapo captain who was imprisoned in Rome, told me shortly before he died that Odessa is a myth. “I always say that Odessa is the invention of an Englishman,’ he said, referring to Frederick Forsyth. “I would have been lucky if somebody had helped me, but there was no Odessa.” Priebke cited the lack of financial assistance he received as evidence that the group did not exist.

Frederick Forsyth first heard of the story from an article in the Sunday Times written by Antony Terry in July 1967, in which the function of Odessa was described, and how its greatest coup had been the rescue of – who else? – Martin Bormann. Terry’s source for the story was none other than Simon Wiesenthal. Had Terry’s editor known that the ultimate source of much of the piece was a duplicitous former SD man called Wilhelm Hoettl, then he might have put the article on the spike.

Or probably not. After all, Odessa, as Frederick Forsyth knows, is a great story.

Someone needs to write a book (although I think an Italian may have done so on Merano and the Alto Adige (or Sud Tyrol as you may prefer); the place was rife with lovely people. Or at least pull all the information about the Merano/Rome/Genova connections.

Most organisations of former SS men were more interested in lobbying the West German government to pay them military pensions, than smuggle them to South America. The fact that many of the Nazis who did make it abroad lived in relative poverty, would also seem to mitigate against the existence of a secret organisation (of former SS men) bankrolling them.