Aaaah, the sexy and seductive female spy – surely there is no more tempting figure for a writer to include in a potboiler? And better still, how about a sexy and seductive female spy who is also – to use the term of the period that is about to be in question – an ‘exotic dancer’? (Mind you, I’m not sure I have the right to be sniffy – I featured such a character in my first potboiler work of genius, The Traitor.) But surely what’s even better is if our lady isn’t a fictional creation, but a real life human being, and what’s more a woman whose actions changed the very course of the Second World War.

Let’s step back to the Cairo of 1942. The Egyptian capital is teeming with soldiers, war correspondents, and secret agents, and attending to their whims is a whole army of women. Among them is a young Jewish woman who calls herself ‘Yvette’, and who plies her trade from the Dug Out Bar of the Metropolitan Hotel.

One night in July, Yvette is approached by a handsome Egyptian man, and along with another woman, Yvette and her new companion spend the night on a houseboat having a good time. They are joined by the man’s friend, and the following morning, the friend hands Yvette £20 in British banknotes – the equivalent of some £1,000 in 2022.

So far, so normal. But Yvette is not all that she seems. In fact, she is actually a secret agent working for the Jewish Agency in Egypt, and she informs her masters that she has her suspicions about her handsome new friend.

“The man I was with last night,” she reports. “He says he is an Egyptian, but I am sure he is a German. I heard him talking to his companion, and he spoke with a Saarland accent. He is very nervous and he has too much money.”

As it turns out, Yvette’s hunch is absolutely correct, for her companion is none other than Johannes Eppler, a German spy sent to Cairo by none other than Rommel himself to find out about British plans. The mission is inevitably named Operation Kondor, and Eppler’s friend is his fellow agent Hans-Gerd Sandstede. Over the next few days, Yvette inveigles herself into the world of these two Nazi spies, until one day on the houseboat she find the proof she needs.

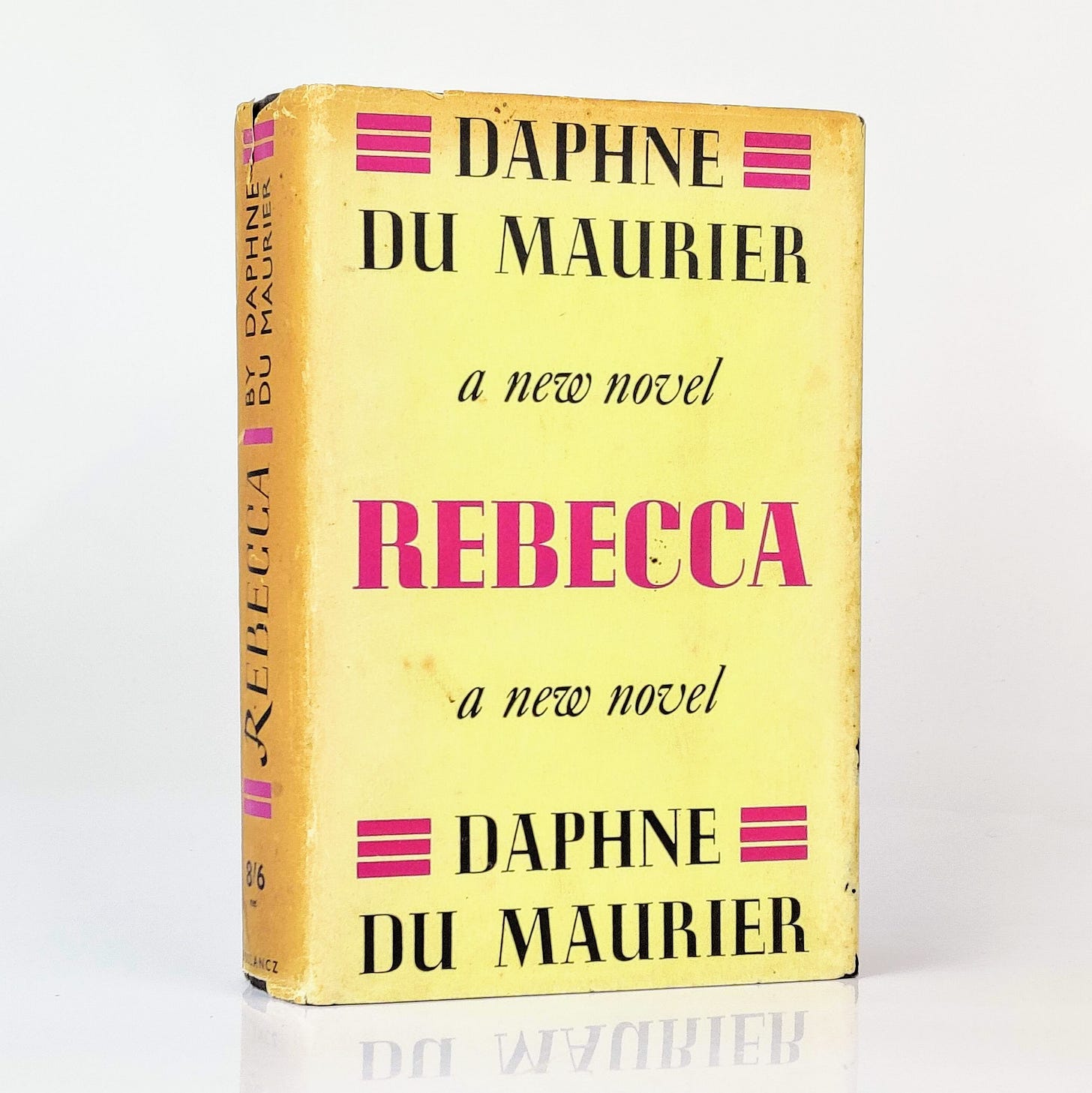

It comes in the unlikely form of a copy of the novel Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, which Yvette leafs through and notices that the pages have been augmented with some sort of grid. She quickly realises that she has a code book in her hands – absolute proof that the two men are spies.

Yvette hurries to the British intelligence services, and within hours, the two men have been arrested, and the code book is on its way to Bletchley Park. There, the boffins crack the code, and by impersonating Eppler, the British are able to send the Germans reams of false information that deceives Rommel sufficiently to give Montgomery the upper hand at the decisive battle of El Alamein, which turns the tide of the war in North Africa.

After her momentous role, Yvette decides to retire from the two oldest trades in the world, and returns to Israel, where, in the words of one account, she raises ‘a magnificent family’.

It is of course a brilliant story – and it would be even better if it were true. Sadly, the whole story is almost complete crap. For while there indeed was a secret German mission featuring Eppler and Sandstede, there was no ‘Yvette’, or indeed a copy of Rebecca found on a houseboat.

So where does the story come from? And what is the truth?

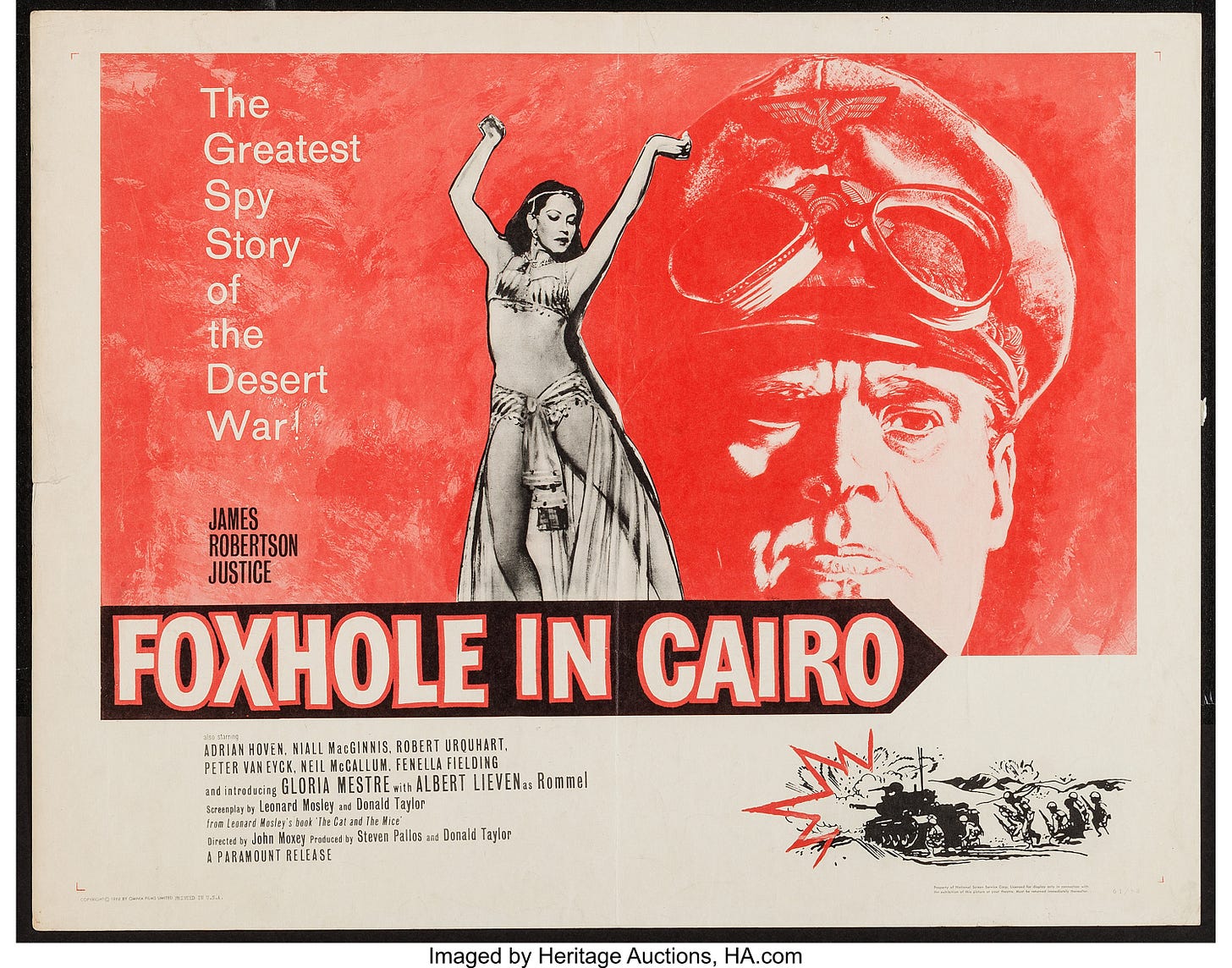

The culprit is the author and journalist Leonard Mosley. A quondam assistant manager of a burlesque show, Mosley wrote many books, including The Cat and The Mice, an account of the Eppler case written in 1958. It was there that Mosley featured the story of the resourceful ‘Yvette’, which titillated enough readers to ensure that the book was turned into a film in 1960 called Foxhole in Cairo, starring Fenella Fielding as Yvette.

Since then, the story of ‘Yvette’ has lived on, and appears in numerous books and websites, which I won’t name because it just seems petty. The Eppler case did, however, form the basis of Ken Follett’s thriller, The Key to Rebecca.

So how do I know the story is fictitious?

The answer is simple, and it lies in Eppler’s MI5 file held at the National Archives in Kew in the UK. If you leaf through it, you will not find a single mention of ‘Yvette’, or of a code book disguised as Rebecca. And neither will you find ‘Yvette’ in Eppler’s own published account of the mission, Rommel's Spy: Operation Condor and the Desert War. What you will find is a figure called ‘Edith’, who plays a similar role to ‘Yvette’, but that simply cannot be true as she too does not appear in the MI5 file.

The true story that emerges, however, is no less fascinating.

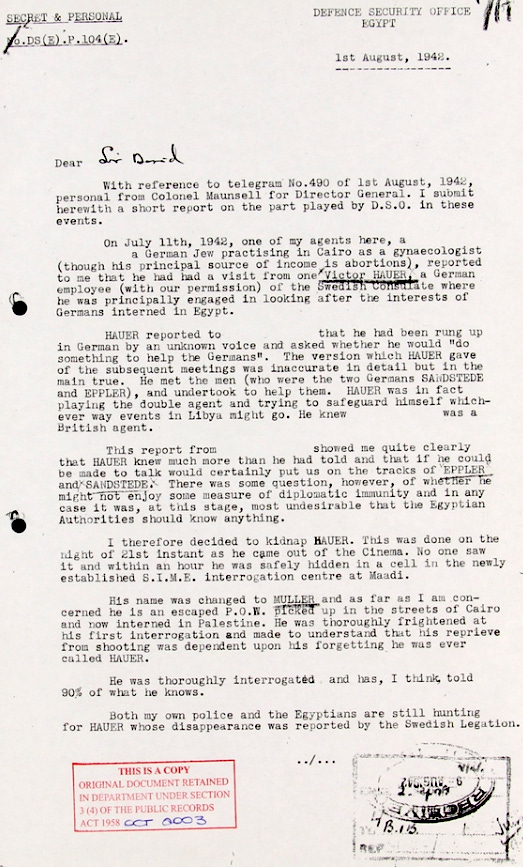

The reason why the British rounded up Eppler and his associates was because they were betrayed by a fellow German called Victor Hauer, who worked at the Swedish Embassy in Cairo looking after the interests of German internees. The British Defence Security Office (DSO) had been contacted by one of their sources, a German Jewish gynaecologist, who had been told by Hauer that he had been approached by two Germans – Eppler and Sandstede – who had asked him to help with their espionage activities. Hauer was then kidnapped by the British, and he told them what he knew.

Shortly afterwards, the British rounded up the spy ring, which included – in a lovely euphemism – ‘a large collection of people mostly of doubtful antecedents’.

Doubtful these people most certainly were, but perhaps the most doubtful of all was a woman who was clearly the basis for the fictional ‘Yvette’.

Her name was Hekmat Fahmi, an occasional movie actress and the glamorous belly dancer at the Continental Hotel, and who had been introduced to Eppler by the head waiter of the hotel’s roof garden.

Just as with the story of ‘Yvette’, the Germans did indeed spend the night on a houseboat with Fahmi, but when she was questioned by the British she denied having slept with Eppler, or indeed of spying for him. Eppler also denied that Fahmi worked for him, claiming that she was ‘a very ignorant girl who knows nothing outside of dancing, drinking and the etc’ – one can only guess what Eppler meant by ‘the etc’ – and that she could not ‘possibly understand any conversation relating to military matters’.

The interrogators didn’t believe it for a moment, not least because they found some secret plans of Tobruk on Fahmi’s houseboat. Worse still for Fahmi, Sandstede’s diary revealed that it was her who had obtained the plans.

When questioned about the plans, Fahmi claimed that they merely belonged to her lover, who was an ‘English officer who was away in the desert’.

Thanks to the MI5 file, we know the name of Fahmi’s paramour – one Captain (Nigel) Guy Bellairs, who worked for the Special Operations Executive (SOE), and who has a file at the National Archives in Kew, which I have yet to consult. Little is known of Bellairs, although he appears to have been wealthy and after the war emigrated to South Africa where he sold telecommunications systems for mines, and in 1960 had a son called Russell Guy Bellairs, who now runs a firm called Drainmaster in Devon in the south west of England.

It is not clear whether Bellairs wittingly supplied Fahmi with the documents, which would have been treasonous. Even with the benefit of the doubt, it was astonishingly slack of Bellairs to have left a case of military plans on a houseboat belonging to an Egyptian belly dancer.

Whatever the truth, the British were certain that Fahmi had helped Eppler, and that certainty was to be proved right by Eppler himself, when he later admitted in his book that he not only slept with Fahmi, but that she had agreed to work for him. His appreciation of his lover is worth reading:

For her pains, the British locked Fahmi up for a year, while Eppler and Sandstede were treated as political prisoners and escaped the noose, for reasons that are too long to explain here, but can be found in Eppler’s book. After the war, Fahmi tried to return to dancing and acting, but as she was approaching forty, she found that she had been usurped by a younger cohort of dancers, and she instead concentrated on raising her family with her husband, the director Mohamed Abdel Gawwad. She died in 1974.

It is a shame that the true story of ‘Yvette’ has been buried by journalistic invention – and also by Eppler’s own fictitious ‘Edith’. It is possible that both Mosley and Eppler created this glamorous Jewish agent in order to mask the true story – that the British had thoroughly penetrated the spy ring because a German had betrayed them.

Still, what is so great about this little tale is that in the form of Hekmat Fahmi we really do have a seductive female spy, and she was very real indeed.

Section viii (MI6). Working in the Embassy and in SLU (Special Liaison Units - a Morris C8 Truck with wireless radios) Transmitting and receiving ULTRA for Monty. Will post pics.

My Dad was in Cairo in 1942. MI6. (Taps nose)